It’s hard to overstate the importance of Arctic research to Canada. Of our over 250,000 kilometers of coastline, over half of it is in the Arctic. A quarter of the total Arctic territory lies within our borders. And given that the earth’s polar regions are experiencing the effects of climate change faster and more dramatically than anywhere else, it’s only right that we should be at the forefront of scientific efforts to understand what’s going on. This week, those efforts were on display in a big way, as over two thousand researchers from around the world gathered in Montreal to share results from the International Polar Year 2007-2008 (IPY).

The Jellyfish Chronicles

You’ve probably read the headline hundreds of times: Human Activity Threatens Survival of Species X. Given nature’s seemingly boundless creativity, you might well start to wonder if there isn’t, somewhere on the planet, a group of creatures for which all this anthropogenic activity might actually be a blessing, rather than a curse. A new study from the University of British Columbia may just provide the answer, in the form of the humble jellyfish.

Trans-Canada Slimeways

Regular readers of this blog (I flatter myself that such people exist) will know I’m keen on slime moulds, a form of life that defies easy description. So the publication this week of a paper that show how a particular type of slime mould can model transportation networks in Canada was simply too good to ignore. Not only does the research explore important questions about how nature performs computations, there’s also a cool YouTube video showing a time-lapse of the cool/gross slime in action. What could be better?

Clearing the Air on Chlorine

Earlier this week, I was forwarded the following video from SunTV. In it, Ezra Levant interviews self-confessed Greenpeace dropout Patrick Moore about a supposed controversy over a very common chemical: vinyl.

Climate Change Hits Where it Hurts: Hockey

I know I’ve been writing a lot about climate change lately, and I promise that after this post I’ll try to switch it up a bit. But in my defence, for a blog about Canadian science, it doesn’t get any more relevant than this: a group of researchers from Concordia University and McGill University have published the first evidence that climate change is having a measurable impact on our treasured national pastime of outdoor hockey.

Of Carbon, Coal, Climate, and Clarity

Andrew Weaver of the University of Victoria is one of Canada’s more outspoken scientists, and in the past two weeks he’s done even more speaking out than usual. First, it was the federal government’s alleged muzzling of scientists. Then on Sunday Weaver, along with PhD candidate Neil Swart, published a commentary in Nature Climate Change which showed that the potential global warming from Alberta’s oil sands is actually quite small compared to that from other fossil fuel sources, such as coal and natural gas. That may sound surprising, but it shouldn’t. The numbers weren’t exactly new; it’s the way Weaver and Swart presented them that made all the difference. And despite what some may argue, this study in no way provides a green light for oil sands development. Weaver is obviously a busy guy, but I did manage to talk to Neil Swart earlier this week. Here’s the story behind the latest paper.

Continue reading

Come Talk to Me: Un-Muzzling Government Scientists

Besides the rare and welcome chance to reference Peter Gabriel in a blog post title, today’s topic allows me to address an important issue that had been bugging me and all members of the Canadian science journalism community for quite a while: why is it so hard to talk to federal government scientists about their research?

The problem is not new. One of the first to sound the alarm was Andrew Weaver, a climatologist at the University of Victoria and, as part of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize. As early as 2008, he was alleging that Canadian government scientists were not free to speak to the media as they saw fit. Since then, a string open letters and editorials has flowed forth from all quarters: Kathryn O’Hara, then president of the Canadian Science Writers Association (CSWA) wrote a major piece in Nature in September 2010. CSWA issued its own open letter during last spring’s federal election. Last fall Bob MacDonald joined in the fray, and parliamentarians like Ted Hsu and Elizabeth May have weighed in as well.

RSC Sounds Alarm Over Canada’s Ailing Oceans

The Royal Society of Canada (RSC) is kind of a big deal, composed of Canada’s most distinguished scholars, scientists and artists. These are people who know an awful lot about an awful lot, and when they have something to say, it’s probably a good idea to listen. Yesterday they spoke out about the way Canadians are managing their ocean territories. Their message: we need to seriously clean up our act.

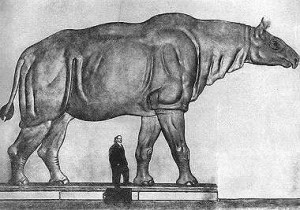

The Speed of Size – Evolutionary Rates in Mammals

About 65 million years ago, our nearest ancestor was probably something small, scuffling and more rat-like than you may be comfortable with. But after a giant asteroid wiped out practically all of the dinosaurs (excepting those which became birds) mammals were suddenly free to take up new lifestyles. 30 million years later, they had produced Baluchitherium, a rhinoceros-like creature twice the size of a modern elephant. Just how fast can an evolutionary group increase in size, and how fast could they do the reverse? Jessica Theodor has an answer. She’s an associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Calgary, and one of about 20 authors on a major paper published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

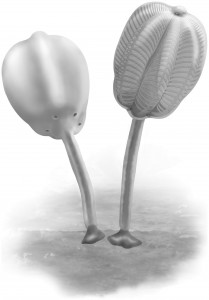

Unpressing the Flower – a New Burgess Shale Species

This week, Lorna O’Brien realized what may well be every paleontologist’s dream: to be the first to describe a brand-new species. Hers is a slightly odd, stalked, filter-feeding creature which looks uncannily like a tulip, named Siphusauctum gregarium. It was found in strata from the Burgess Shale, Canada’s Cambrian fossil goldmine, which continues to produce new discoveries at regular intervals. “There’s been so much work done on the Burgess Shale in the past 100 years,” says O’Brien, a PhD candidate in Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto and the Department of Paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). “When I was an undergrad, I never thought I’d get the opportunity to name a Burgess Shale animal, so in that sense it’s been incredibly exciting.”