This week, Lorna O’Brien realized what may well be every paleontologist’s dream: to be the first to describe a brand-new species. Hers is a slightly odd, stalked, filter-feeding creature which looks uncannily like a tulip, named Siphusauctum gregarium. It was found in strata from the Burgess Shale, Canada’s Cambrian fossil goldmine, which continues to produce new discoveries at regular intervals. “There’s been so much work done on the Burgess Shale in the past 100 years,” says O’Brien, a PhD candidate in Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto and the Department of Paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). “When I was an undergrad, I never thought I’d get the opportunity to name a Burgess Shale animal, so in that sense it’s been incredibly exciting.”

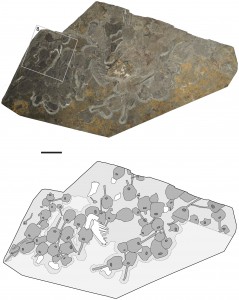

As I mentioned in a previous post, the Burgess Shale is located in British Columbia’s Yoho National Park. It is the world’s richest source of well-preserved fossils from the Cambrian period, which stretched from about 540 to about 490 million years ago. But it would be misleading to think of it as a single location; in the past 100 years over a dozen new sites have been added to the original Walcott quarry. In 1983, a ROM expedition uncovered a set of rocks chock full of the fossilized creatures O’Brien has just described. There were so many – over 1100 in all – that the area is known as the Tulip Beds. O’Brien first saw it for herself in 2010. “It’s quite impressive; we have slabs that have up to 65 individuals that are just sort of folded across each other,” she says. “You can clearly tell that they’ve just had a big pile of sediment dumped on them. They’ve been flattened pretty much in their life position.”

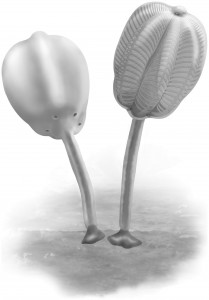

Upon returning to the ROM, O’Brien began the long process of examining each one of the specimens in meticulous detail. She looked at the rocks under water, under microscopes, and under polarized light. She made thousands of detailed drawings and miniature clay models. She then worked with paleoartist Marianne Collins to turn the 2-D pressings into a 3-D conception. “We had un-press the flower,” says O’Brien. “That was probably the most challenging part, and I often needed to go back to the fossils to answer questions about how things fit together.”

In the end, she developed a conception of a creature ranging in length from a few centimetres to almost a foot, anchored to the sea floor with a long stalk. Although it looks like a tulip, it is very much an animal, with a bulbous body – called a calyx – containing an intricate six-rayed filter-feeding system. The animal would have sucked in water at the base of the bulb, captured the nutritious plankton, and squirted the rest out the top. Their lifestyle resembled that of modern-day animals like sea pens, although they are no relation.

In fact, it is their very filter-feeding nature that makes them hard to classify. According to O’Brien, being a filter-feeder restricts the kinds of shapes an animal can have. As a result, non-related species can look more similar to each other than ones that are closely related but have different lifestyles; this is called convergent evolution. Partly because of this, O’Brien has refrained from lumping S. gregarium in with any modern animal groups. “Probably its closest relative was Dinomischus,” she says, referring to another Bugess Shale animal. “It would probably be like a miniature cousin of Siphusauctum. But I just couldn’t confidently place it on any stem lineage, and I would prefer to say we just don’t know.”

The unresolved nature of S. gregarium points to the fact that even after more than a century of work, there are still plenty of Burgess Shale mysteries left to be solved. As for the discovery of even more new species, O’Brien has no doubts. “There are absolutely more species to be found, and I think the better our understanding of the fossils that we already have, the better we’ll be able to interpret the new animals that are still out there.”

Unsurprisingly, I’ve not been the only one to write about this discovery. In researching this story, I came across the remarkable blog of a seven-year-old boy named Art, who already knows more about Cambrian paleontology than I ever will. His post on S. gregarium contains lots of anatomical detail I didn’t have room for. 50 bucks says he’ll discover a Burgess Shale animal of his own in about 20 years.

No comment yet, add your voice below!