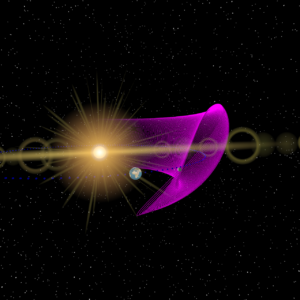

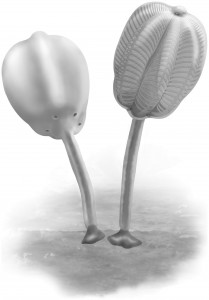

This week, Lorna O’Brien realized what may well be every paleontologist’s dream: to be the first to describe a brand-new species. Hers is a slightly odd, stalked, filter-feeding creature which looks uncannily like a tulip, named Siphusauctum gregarium. It was found in strata from the Burgess Shale, Canada’s Cambrian fossil goldmine, which continues to produce new discoveries at regular intervals. “There’s been so much work done on the Burgess Shale in the past 100 years,” says O’Brien, a PhD candidate in Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto and the Department of Paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM). “When I was an undergrad, I never thought I’d get the opportunity to name a Burgess Shale animal, so in that sense it’s been incredibly exciting.”