Erick James spends his days investigating the contents of termite intestines, a line of work that you’d think would relegate him to obscurity. But thanks to a bit of clever marketing, James, who works in the biology lab of Patrick Keeling at the University of British Columbia, has garnered attention from countless blogs and even some major newspapers. His latest discovery — a microscopic organism that helps its termite hosts digest their woody meals — is interesting on its own, and could have implications for industries like biofuel. But what has attracted all the attention is the fact that James named his pet organism after a fictional monster that has become a powerful internet meme.

If you’re already up to speed on the tentacled horror that is Cthulhu (James pronounces it kuh-THOO-loo) you can skip to the next paragraph. If not, you need to know that the character was originally introduced by writer H.P. Lovecraft in his tale “The Call of Cthulhu,” published in the pulp magazine Weird Tales in 1928. Cthulhu is supposedly an ancient cosmic entity with a humanoid body, a face that resembles an octopus (albeit with far too many tentacles) and bat-like wings, for good measure. He sleeps beneath the mythical city of R’lyeh until someone accidentally releases him to, you know, destroy the world. Personally, I’ve always found the idea a bit too preposterous to be scary, but Cthulhu has clearly caught on in the pop culture imagination: a quick internet search reveals vast quantities of Cthulhu-themed art, comics, t-shirts and other geeky items. James cites in particular an episode of South Park and a Dr. Seuss-like series of illustrations as his introduction to the character.

Ok, back to the termites. Despite appearances, termites don’t actually digest wood. Instead, they rely on endosymbionts – microscopic organisms living in their gut – to do this for them. “There are two types of termites: higher and lower,” says James. “The higher termites use bacteria and fungi to break down the wood, but the lower termites use protists.” The term protist is a kind of biological catch-all for single-celled organisms that can’t clearly be classified as animals, plants or fungi. Many of them swim around using appendages called cilia or flagella; the best-known example is the amoeba. They can live in just about any environment where there’s enough moisture, but it turns out that termite intestines are a place of particularly rich diversity. “Each termite species will have four to seven genus levels of endosymbionts, and within each of those, there can be several species,” says James.

The endosymbiont community varies by species, not location. In other words, two termites from the same species collected in different parts of the world will have very similar endosymbionts, but two unrelated species living in the same area will have very different ones. Of course, termite species can be frustratingly hard to tell apart; James relies on Rudolf Scheffrahn, a termite expert at the University of Florida, to tell him what termites he’s looking at — or more precisely, into. “Sometimes we put them in ether, just to get them a little sleepy, so they’re not running around as much,” says James, who doesn’t seem very sentimental about the creepy little insects. “Then we unceremoniously rip out their intestines and put the contents under the microscope.”

The bible of termite-protist-hunting is a 1979 review article by Michael Yamin, which has since been published as a book and which documents all species known at that time. James compares everything he sees in the microscope with that article, plus a few updates published over the last few decades. If it’s not in any of those, there’s a good chance it’s a new species, but he first has to check by sequencing the 16s ribosomal RNA, which is a kind of genetic barcode for all organisms. Assuming the online databases don’t turn up any matches, James has got a new creature on his hands. That’s just what happened with Cthulhu, or to use its full name, Cthulhu macrofasiculumque.

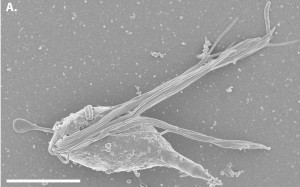

As described in an article published in the journal PLoS ONE, Cthulhu is a medium-sized protist with a thick bunch of flagella which lives in the lower gut of Prorhinotermes simplex, a termite endemic to southeastern Florida, western Cuba, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico. “We had never seen anything like it, and neither had our collaborators,” says James. Cthulhu swims by whipping its flagella back and forth, looking for all the world like a tiny squid, octopus or, if you squint your imagination, terrifying ancient cosmic monster. James also found a smaller but similar-looking protist in another, more common species of termite, Reticulitermes virginicus, that lives across the US and into Canada. Recognizing it as a sister-species to Cthulhu, he searched online for stories about related monsters, and eventually went with Cthylla, after a story that describes Cthulhu’s supposed daughter. Interestingly, Cthylla’s 16s RNA was already in the database, labelled “unknown environmental sequence.” It was only after James’ investigations that this sequence could be given a name.

Cthulhu macrofasciculumque swims by whipping it flagella back and forth, similar to the motion of a squid or octopus.

No comment yet, add your voice below!