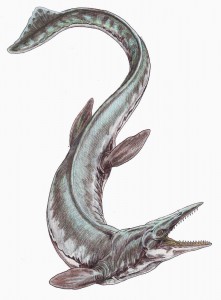

Erick James spends his days investigating the contents of termite intestines, a line of work that you’d think would relegate him to obscurity. But thanks to a bit of clever marketing, James, who works in the biology lab of Patrick Keeling at the University of British Columbia, has garnered attention from countless blogs and even some major newspapers. His latest discovery — a microscopic organism that helps its termite hosts digest their woody meals — is interesting on its own, and could have implications for industries like biofuel. But what has attracted all the attention is the fact that James named his pet organism after a fictional monster that has become a powerful internet meme.