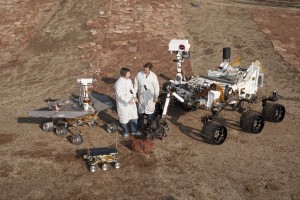

I can feel the atmosphere heating up, and it’s more than just the sweltering August weather. The next few hours will either make or break the mission for the Mars Science Laboratory, better known as Curiosity. Just after midnight, it will attempt to land in the Gale Crater that straddles the border between the northern lowlands and southern highlands of Mars. It’s by far the biggest Mars probe to date: at more than half a tonne it’s the size of a subcompact car. And while the landing itself has attracted most of the attention, it’s really just the beginning of an exciting international scientific collaboration, one in which many Canadians are playing a prominent role.